Games Workshop - Part 2

Readers, welcome back. In Part 1 of this series, we looked into the origin story of Games Workshop and its development through the late 1970s, the 1980s and how it was taken public by Tom Kirby in 1994. In this post, we will continue on this thread but for better context and for those who haven’t done so already, I would encourage you to read Part 1 first. Let’s dig in.

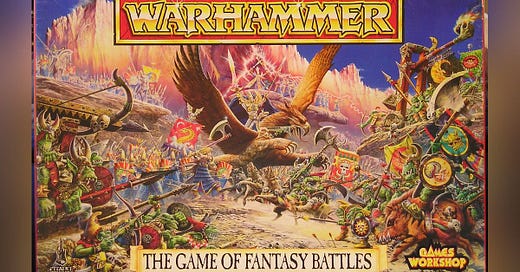

So, during the first half of the 1990s GW starts focusing even more on their own miniature wargames Warhammer Fantasy Battle (WFB) and Warhammer 40,000 (WH40k), their most lucrative lines.

Their audience also changes, increasingly targeting a younger and more family-oriented crowd. The strategy works and enables the Company to expand internationally into new territories, into mainland Europe, the US, Canada, and Australia.

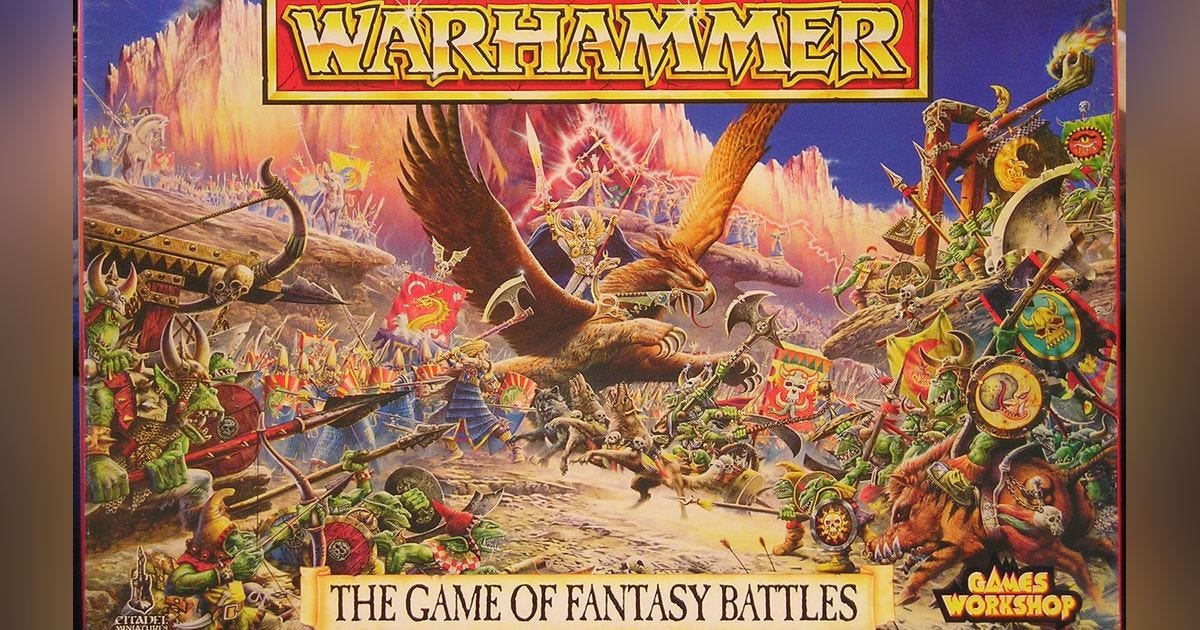

In the late 1990s, in 97, GW starts a new publishing program: the 'Black Library'. It’s mostly an initiative by Tom Kirby and will become a fully functioning commercial publishing house within the GW group of companies, feeding the Warhammer World. The same year the Company launches a magazine of original Warhammer fiction called Inferno!, a bi-monthly magazine. Two years later, in August 1999, GW begins publishing new Warhammer novels under their new imprint and would soon republish older titles too.

I am big fan of this strategy. You can see how the Company is cultivating the brand, how the Warhammer world is being expanded into different directions, through different forms of media. GW keeps coming at customers, engaging them from all angles. From games to novels to characters, feeding on each other, creating this highly engaging fictitious world - a world that Games Workshop creates and controls. So, the Company starts cross selling into other product lines. Just to give you a feel for how powerful this is, in the early 2000s, 50-60% of all US sales are to people who aren’t even familiar with the games to begin with. That to me is the power of having your IP across multiple channels all working towards one center of gravity.

In the years that follow, the core business starts growing like a train. By that time, and over the past ≈ 25 years, the Company has become multinational, was listed on the London Stock Exchange and starts generating sales in excess of £100 million. That’s a long way from student-enthusiast mail ordering origins, isn’t it?

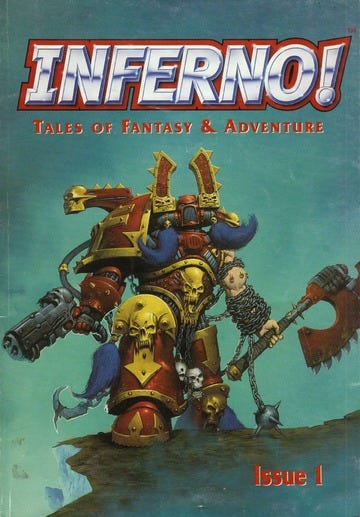

Business is rolling ahead nicely and in 2001 things get even better. Games Workshop starts promoting games associated with The Lord of the Rings film trilogy, acquiring the rights to produce Lord of the Rings tabletop games. And it’s beautiful. With the Lord of the Rings IP, it starts reaching new communities, investing in gaming events and ultimately helping to grow a generation of miniatures-loving geeks.

The Company starts combining its influence on popular fiction Warhammer and fantasy video games, aligning its products with the very popular Lord of the Rings movie series to attract new gamers. And slowly but surely the miniatures morph from something sitting in your shoe box to rarefied collectibles with practical purpose in gaming culture. This miniature-oriented tabletop gaming culture created an appreciation for high-quality tabletop gaming components, the very thing GW had to offer.

The Company has such desirable IP with the Warhammer franchise at the turn of the millennium that it starts placing characters into the digital gaming world. In the early 2000s it enters into a licensing agreement with THQ and by 2011 THQ has published several successful titles including Warhammer 40,000: Dawn of War, a real-time-strategy game for PC that shipped 6.5 million to that date. A game for the Xbox 360, PlayStation 3 and another PC set Warhammer 40,000: Dark Millennium Online, a massively multiplayer online game exploring the deep fiction and myriad races of the IP, would follow. However, the licensed IP, in terms of pounds and pence, turnover and profits, under Tom Kirby just doesn’t move the needle for the overall business.

Yet there is another great push by the Company to plant the Warhammer seed into people’s minds. During the 2000s, GW is hosting multiple Games Days, all over the world. They are in Cologne Germany, Paris France, Toronto Canada, Atlanta, Baltimore, Chicago USA, Barcelona Spain, Milan Italy, Birmingham UK, Sydney Australia and Vianna Austria.

At these Games Days, attendees have the chance to meet artists and game designers, participate in terrain-building workshops, and play games against Games Workshop store employees. There are competitions and interactive activities. This was a great move as this served as platform for gaming enthusiasts to engage in creative pursuits, interact with industry professionals, and explore a diverse array of gaming-related merchandise. Again, do you see the emotional tie the Company is building with its customers here? It’s all based on fun. They are adding tremendous value for the players.

So between 1996 and 2004 GW is on an absolute run. It grows at 20% compounded annual growth rate and it grows profitably. As mentioned, the Company expands internationally, Black Library is launched, Lord of the Rings boardgames and miniatures are released, gaming events are being held and the frequency of publications keeps increasing. Things are going great. Annual sales are less than £15 million in the early 1990s. By 2002 they grow to £100 million and in 2004 they peak at over £150 million. 10x in 10 and a bit years. What a rocket.

And then…

…the engine starts losing steam. From 2004 onwards sales start to decline until they hit their low point in 2007 and 2008 at around £110 million. The former glory days are starting to fade into the background and more and more critics are creeping up.

At the time some commentators say Tom Kirby lost his focus. To me, that statement lacks granularity as we shall discover later on in the series. It doesn’t take the Company’s history and context into account, the strategic developments underneath and overall, it’s short sighted. Tom Kirby, then-CEO, years later, in his 2012 annual shareholder letter makes an interest comment in relation to that period, giving you an insight into his mode of thinking:

“My favourite graph in our internal reporting shows the sales in each country going as far back as we have records. 1988, I believe. The really great part about it is that it has over 20 years of data. You can see proper trends over 20 years, and if your intention is to build a business that lasts, which mine always has been, then ‘long term’ means decades. What does the graph show? It shows our rapid increase of sales in the 90s when we opened a lot of stores in the UK and a lot of businesses around the world. The UK line then shows a period of consolidation as that growth demanded we sort out our manufacturing and warehousing. Then we enter a short surge due to our intoxicating Lord of the Rings tie-in (everywhere except the US, interestingly enough) followed by a long hangover in Europe and a shorter one in the UK.”

Nevertheless, in the late 2000s, some commentators are saying that hobbyists are turning their backs on GW as they feel that the identity of the Company is being lost; some are even talking about real reputational damage. Other critics say Tom Kirby ignores the monetisation opportunity of the IP and that the Company is lacking a clear strategy. In their defense, numbers don’t lie. The company has less revenue in 2016 than in 2004. Only in 2017, it took 13 years until the Company starts hitting its 2004 sales number again.

So, I’ve dug around, and found a former Games Workshop designer, Tuomas Pirinen. Tuomas worked for the Company but also for Electronic Arts, Ubisoft and Remedy - big reputable names, clearly, he has seen things in the industry from within and is in a position to make comparisons. Here are his thoughts in 2016 regarding the performance of GW in recent years (at that time revenue is still below 2004, so no growth over 10 years):

“While these are still exceptionally impressive sales for almost any games company (and with healthy profit margins too), it is clear that the current approach is not generating growth and expansion of the hobby. It could of course be down to competition, but the magic of the huge growth curve from 1990 to 2003 just isn’t there anymore no matter how you slice it, and in my heart of hearts I am not sure if it had to be this way.” … “I would say it was perhaps more of a question of not holding on to the talent rather than pushing them away. I have learned in many companies since then how much effort you need to put into talent retention.” … “GW in my days was willing to try anything, while now it seems to be turning inwards and doubling down on the safer bets.” … “And Rick was the most instrumental person and the secret sauce behind this huge success. [Rick Preistley was the person that Brian Ansell turned to and asked to develop a medieval-fantasy wargame that ultimately became Warhammer] and I will stand behind this statement against any man or woman who says otherwise.” … “Tom bought the original GW from Mad King Bryan Ansell, [Bryan Ansell was in Charge of the original Citadel, the miniatures company that later bought out the original founders Ian and Steve and the firm] who with Rick essentially created the heart and soul of GW. Tom has a very good understanding of scaling and finances. However, as the company grew, it focused more and more on corporate aspects and cost-cutting, while whittling down the Old Guard, out of whom only Jes Goodwin Alan Merrett and Jervis are still there. My own feeling is that it was a few cuts too deep, and the company lost a lot of its vitality and ability to take risks and do mad things that lead into new success stories. This is of course very common whenever a company gets larger. Note that these are my views, and someone like Rick would have far better idea of what exactly took place. I do not think Tom tried to sabotage the company at all, quite on the contrary.”

At the time some gamers are sensing Tom Kirby’s lack of fundamental gamers’ enthusiasm for the underlying games. He didn’t do himself any favors with comments like these: "some people are born with the need of buying little models to paint, we provide them". Of course, the statement is factual, but it isn’t exactly inspiring; it lacks soul, purpose and excitement, especially for a product that is so heavily built on emotions.

Other gamers commented with the following at the time: the rules of the game started being unusable, the game suffered. The prices kept growing. Official online forums were being closed down. The company became unreachable from the outside. Under Kirby the story stagnated for 20 years, then it was let carry on, when Tom left [and Kevin Roundtree takes over]. Some think it was a good idea, some that it was bad, or badly implemented, but it did revitalised the lore and the game. When Kirby was running the show there was no social engagement, there were no interesting products. There was no care for balancing. It just jacked up the prices until people stopped paying.

The mighty Games Workshop has lost the shine of its glory days - so it seems.

But the story isn’t over yet. To be continued.